Most families have a few old stories that contribute to the chronicle of its history. These accounts, usually handed down verbally through the generations, might include an ancestor who was robbed of land or possessions, descended from a famous person in history or from royalty, or encountered great difficulty on the journey to America. The retelling of the events becomes an integral part of the heritage and tradition of the family. However, the details we know today are probably changed from the original, like in the children’s game of telephone, where a sentence is passed around a circle and invariably is altered when it reaches the last person. Most likely there is some grain of truth in the version we hear, even though it might sound more like legend or myth.

In my family there are numerous stories; however, some of them, unfortunately, have unraveled into bits and pieces in my memory. One such fragment involved a relative who was sick in bed when troops came by the house during the Civil War, an event now over 150 years ago. Where I had heard it, or what relative it included was unclear to me until about 10 years ago. A cousin, Ginny, was working on her Ludwick/Hutchinson family tree. Ginny accumulated a number of documents that she photocopied, put in a binder and kindly gave a copy to my mother. I scrolled through the pages and to my surprise found the story I had heard about the Civil War ancestor. Who actually wrote the story down on paper is unclear, but May 12, 1977 was recorded as the date when my grand aunt Pearl Ludwick related the following:

I can remember when I was a very little girl, Dad told us a story about the Civil War. Granddad (John Ludwick) was very outspoken against the Confederacy. He took every chance he could to speak out against them. When the Confederate Army started north—they followed the Pike (along current day Route 30)—they put out an order to take as prisoners John Ludwick and every member of his family. On the night the first southern soldiers arrived in the area, they stopped at the house of John Ludwick and ordered him and the family to come out. John was very ill in bed but his wife, Esther, came out and begged them not to harm them, as her husband was ill. A shot was fired—went through the wall of the bedroom and lodged in head of bed. The soldiers returned to their camp. In a short while the Southern General came to the house and talked a while with John, Esther and their 3 sons. When he left, he had soldiers bring from his supply wagon, food and clothing for the family. He then ordered his soldiers to march on by as quietly as possible so as not to disturb the ill man.

I don’t know how accurate this depiction is. Pearl mentions she was a very little girl when her father Alpheus told this story to her. Alpheus in turn was about 5 years of age when this event occurred. How precise do we as children remember an incident, especially when recalling it years later? And did the transcriber write this story down as Pearl related it or did they wait a few days or weeks before putting it down on paper? Any of these factors might have altered some of the details.

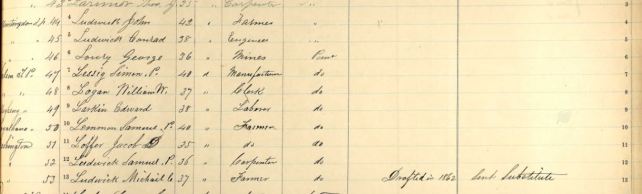

I searched for some information that would help substantiate what occurred. On June 21, 1863 the US Civil War Draft Registration Records for Westmoreland County lists John Ludwick, 42, a farmer living in Huntingdon Township in Westmoreland County. He is recorded beside his brother Conrad Ludwick, 38, an engineer. Further down the page in Washington Township is another brother, Samuel P. Ludwick, and a possible cousin, Michel Ludwick, who was drafted in 1862 but sent a substitute in his place. John’s brother David served in the Civil War and died June 20, 1862 at the Battle of Nelson’s Farm, Virginia. Perhaps this spurred his outspokenness; but was he outspoken against the Confederacy, the draft or the war itself?

In the Draft Registration Records there are no comments written about John, so he probably was not yet ill, nor is there any indication that he was drafted. According to his gravestone, John Ludwick died Feb 9, 1864 at 41 years of age. Although average life expectancy around the Civil War was early 40s, to die at that age, he probably had some serious ailment. The story suggests that John was very ill, perhaps even bed fast as he didn’t get up when the soldiers came. This would put the time frame of the incident between his registration for the draft and his death, probably late fall of 1863.

I explored some records to corroborate Confederate troops making their way into Southwestern PA; as far as I can find they only made it north into Gettysburg in July of 1863, before being driven back. If the Confederacy were in the area, they would have been in enemy territory and to march along a main road would have certainly caused unwanted attention and alarm among the townspeople. Family members might accept the troops that came to arrest John were the enemy, but I suspect it was the Union army. After all Lincoln in the summer of 1862 suspended the writ of habeas corpus, or what some might call due process of law.* This allowed the army to arrest protestors to the draft, or even the war, and to detain them indefinitely without ever being brought before a judge and charged. So an outspoken person, who might have had some influence in the community could have been seen as a threat. It would not have been unlikely for Union troops to be in the area, especially in 1863, after the battle further east in Gettysburg.

The house where the altercation took place was cited as being at the junction of Route 119 and Route 30—the Pike that the troops marched along—although the actual course might have changed over the years. Much of this area, now part of South Greensburg, was owned by the family of Esther Rugh Ludwick. No deed is listed for John and Esther for property in this area, so I imagine that Esther’s family allowed her and her family to live in the house when John became gravely ill. Pearl stated the house was still standing, but by 1977 there were few houses near these cross roads and none that appeared to have been built by the 1860s; the actual site might be a few blocks away and this intersection only a reference point. Someday I hope to determine the house’s actual location.

Whether completely or only partially true, it’s a fascinating and colorful tale. Some incident certainly took place that Alpheus Ludwick witnessed when he was a child. I imagine that there were soldiers, some threat made to the family, a shot fired, his mother pleading and a commander arriving later. Whether he remembered every detail accurately, isn’t as important to me as the fact that he and his family endured this experience. It must have left a strong impression for him to remember it. Lucky for us, Alpheus told his children, who shared it with others and someone in the family had the foresight to write it down so it can continue to live on as an important part of the family narrative.

* Read the entire proclamation at The American Presidency Project